“There’s nothing as practical as a good theory”

‘Cryptic, remote, irrelevant and unusable’: it seemed to us, one term in to Teach First, just as it seemed to the much more experienced Tom Bennett, that practical theories in education were hard to come by. Theories of ZPD (zone of proximal development) and multiple intelligences (from the interpersonal to the intrapersonal) left us with more confusion than clarity.

Over our first year, only one theory has had practical applications that improved our teaching.

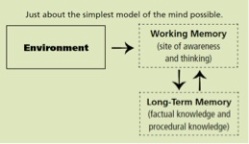

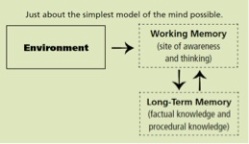

Cognitive science explains how the mind learns, and on that basis recommends how to teach. Its basic tenet is this: minimise working memory overload to maximise long term memory retention.

So here are our six killer apps of cognitivism in education, not just for maths, or only for English, but across all subjects.

The six killer apps of cognitive science

1. Chunks

1. Chunks

Insight: Our working memories are very small (try memorising ‘4687538279201’), but our long-term memories are very powerful, chunking stored information (now try ‘the boy got home’): abstract concepts (like metaphors and ordinal scales) are hard to understand.

Application: Don’t overload your lessons and learning objectives with abstract concepts and complex problems: choose the key question to provoke curiosity, chunk it into very simple tasks and build it up in little bits.

Examples: Instead of ‘by the end of this lesson, students will be able to understand how different dramatic techniques convey action, character, atmosphere and tension’, use: ‘How does the play create tension?’

2. Knowledge

2. Knowledge

Insight: It’s impossible toimprove the skills of reading, critical thinkingand problem-solving without content-specific facts and background knowledge.

Application: Consolidate students’ knowledge foundation securelybeforeyou require higher-order thinking.

Examples: Secure the times tables in Maths, and grammar in English, for instance.

3. Problems

3. Problems

Insight: What makes things interesting to learn and easy to understand is clarifying the problems to be solved.

Application: Focus first on the question or problem type, and the why, before diving into how to solve it. Let students compare and revisit problem types that you’ve covered before, to deepen their understanding.

Examples: Compare lots of GCSE question types in English and Maths.

4. Examples

4. Examples

Insight: Asking students to figure it out for themselves is less effective than showing them how to do what you’re asking, with lots of examples.

Application: Create lots of worked examples so students know how to improve.

Examples: Show lots of model paragraphs in English, and show them lots of step-by-step working in Maths, for instance, how to factorise a quadratic expression.

5. Practice

5. Practice

Insight: It’s impossible to become proficient at any mental task without extended practice.

Application: Drill students in the crucial processes they need to succeed.

Examples: In English, identifying techniques and punctuating sentences, in Maths, manipulating algebra equations and converting between fractions, decimals and percentages.

6. Mnemonics

6. Mnemonics

Insight: Long-term memory storage and retention works best when triggered by chunking.

Application: Createpowerfulmnemonic devices with acronyms for complex, important processes that students need to be able to do.

Examples: Maths teachers have long used SOHCAHTOA for trigonometry; English teachers have used PEEL for textual analysis. Create your own: try ‘SEAL the DEAL’ for comparative writing (Similarity Examples Analyse Link; Difference etc).

Dan Willingham’s Why Don’t Students Like School? is a good place to start exploring these ideas.